Neuromorphic chips are being designed to specifically mimic the human brain – and they could soon replace CPUs

|

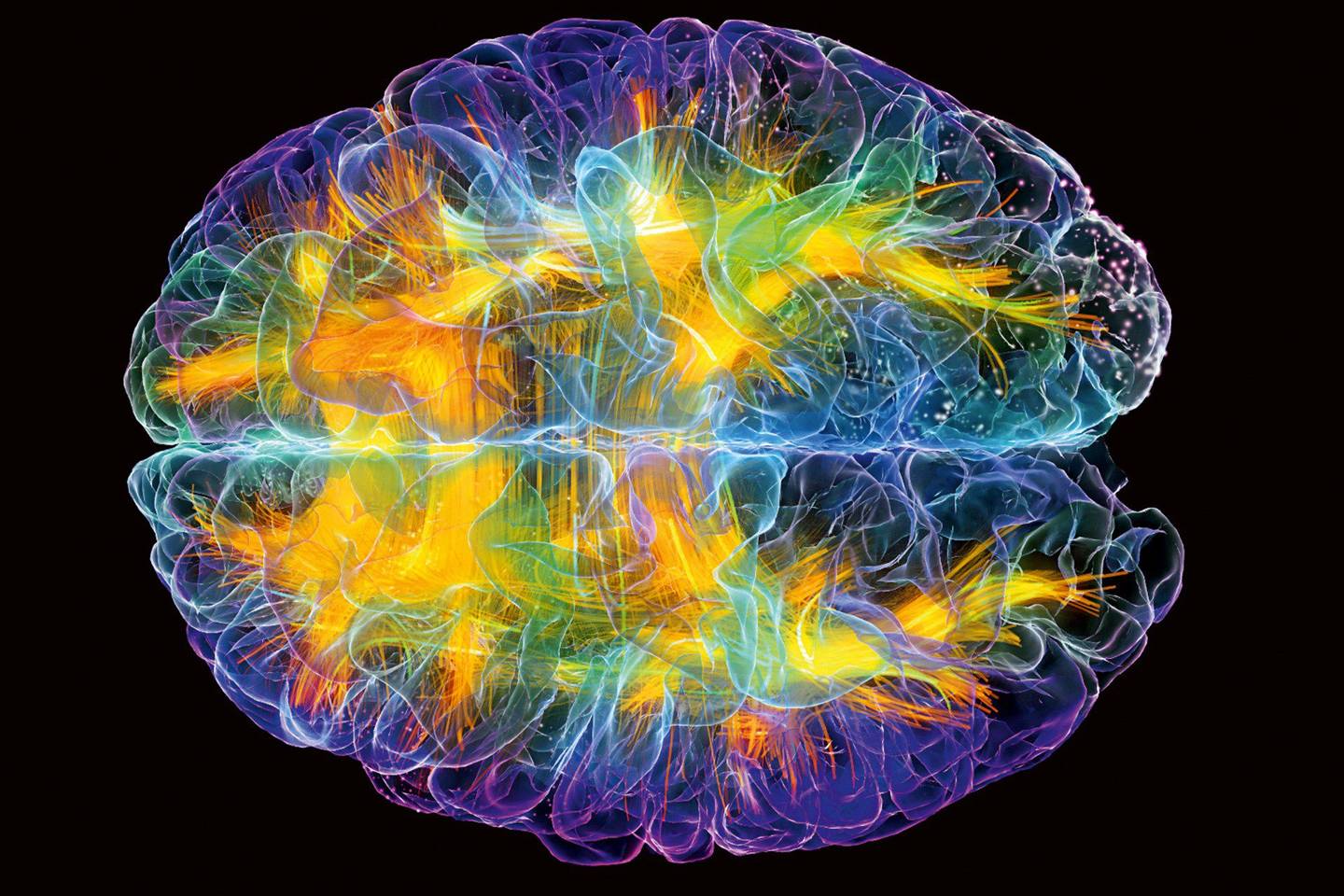

BRAIN ACTIVITY MAP

Neuroscape Lab

|

AI services like Apple’s Siri and others operate by sending your queries to faraway data centers, which send back responses. The reason they rely on cloud-based computing is that today’s electronics don’t come with enough computing power to run the processing-heavy algorithms needed for machine learning. The typical CPUs most smartphones use could never handle a system like Siri on the device. But Dr. Chris Eliasmith, a theoretical neuroscientist and co-CEO of Canadian AI startup Applied Brain Research, is confident that a new type of chip is about to change that.

“Many have suggested Moore's law is ending and that means we won't get 'more compute' cheaper using the same methods,” Eliasmith says. He’s betting on the proliferation of ‘neuromorphics’ — a type of computer chip that is not yet widely known but already being developed by several major chip makers.

Traditional CPUs process instructions based on “clocked time” – information is transmitted at regular intervals, as if managed by a metronome. By packing in digital equivalents of neurons, neuromorphics communicate in parallel (and without the rigidity of clocked time) using “spikes” – bursts of electric current that can be sent whenever needed. Just like our own brains, the chip’s neurons communicate by processing incoming flows of electricity - each neuron able to determine from the incoming spike whether to send current out to the next neuron.

What makes this a big deal is that these chips require far less power to process AI algorithms. For example, one neuromorphic chip made by IBM contains five times as many transistors as a standard Intel processor, yet consumes only 70 milliwatts of power. An Intel processor would use anywhere from 35 to 140 watts, or up to 2000 times more power.

Eliasmith points out that neuromorphics aren’t new and that their designs have been around since the 80s. Back then, however, the designs required specific algorithms be baked directly into the chip. That meant you’d need one chip for detecting motion, and a different one for detecting sound. None of the chips acted as a general processor in the way that our own cortex does.

This was partly because there hasn’t been any way for programmers to design algorithms that can do much with a general purpose chip. So even as these brain-like chips were being developed, building algorithms for them has remained a challenge.

Eliasmith and his team are keenly focused on building tools that would allow a community of programmers to deploy AI algorithms on these new cortical chips.

Central to these efforts is Nengo, a compiler that developers can use to build their own algorithms for AI applications that will operate on general purpose neuromorphic hardware. Compilers are a software tool that programmers use to write code, and that translate that code into the complex instructions that get hardware to actually do something. What makes Nengo useful is its use of the familiar Python programming language – known for it’s intuitive syntax – and its ability to put the algorithms on many different hardware platforms, including neuromorphic chips. Pretty soon, anyone with an understanding of Python could be building sophisticated neural nets made for neuromorphic hardware.

“Things like vision systems, speech systems, motion control, and adaptive robotic controllers have already been built with Nengo,” Peter Suma, a trained computer scientist and the other CEO of Applied Brain Research, tells me.

Perhaps the most impressive system built using the compiler is Spaun, a project that in 2012 earned international praise for being the most complex brain model ever simulated on a computer. Spaun demonstrated that computers could be made to interact fluidly with the environment, and perform human-like cognitive tasks like recognizing images and controlling a robot arm that writes down what it’s sees. The machine wasn’t perfect, but it was a stunning demonstration that computers could one day blur the line between human and machine cognition. Recently, by using neuromorphics, most of Spaun has been run 9000x faster, using less energy than it would on conventional CPUs – and by the end of 2017, all of Spaun will be running on Neuromorphic hardware.

Eliasmith won NSERC’s John C. Polyani award for that project — Canada’s highest recognition for a breakthrough scientific achievement – and once Suma came across the research, the pair joined forces to commercialize these tools.

“While Spaun shows us a way towards one day building fluidly intelligent reasoning systems, in the nearer term neuromorphics will enable many types of context aware AIs,” says Suma. Suma points out that while today’s AIs like Siri remain offline until explicitly called into action, we’ll soon have artificial agents that are ‘always on’ and ever-present in our lives.

“Imagine a SIRI that listens and sees all of your conversations and interactions. You’ll be able to ask it for things like - "Who did I have that conversation about doing the launch for our new product in Tokyo?" or "What was that idea for my wife's birthday gift that Melissa suggested?,” he says.

When I raised concerns that some company might then have an uninterrupted window into even the most intimate parts of my life, I’m reminded that because the AI would be processed locally on the device, there’s no need for that information to touch a server owned by a big company. And for Eliasmith, this ‘always on’ component is a necessary step towards true machine cognition. “The most fundamental difference between most available AI systems of today and the biological intelligent systems we are used to, is the fact that the latter always operate in real-time. Bodies and brains are built to work with the physics of the world,” he says.

Already, major efforts across the IT industry are heating up to get their AI services into the hands of users. Companies like Apple, Facebook, Amazon, and even Samsung, are developing conversational assistants they hope will one day become digital helpers.

ORIGINAL: Wired

By AARON FRANK

Monday 6 March 2017

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario

Nota: solo los miembros de este blog pueden publicar comentarios.